By Patrick Dunning, Associate Editor, Southern Loggin’ Times

PINSON, Alabama – When he was young, not so very many years ago, Kirk Sanders didn’t foresee his future being in logging. He and his big brother Bill had spent some summers working for forester Ken Smith, who was employed at Buchanan Lumber in Montgomery at the time. But a summer job wasn’t necessarily something he envisioned turning into a long-term career.

When he was still a freshman studying mathematics at Montgomery’s Huntingdon College in 1981, Sanders enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserves as an infantry rifleman attached to the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marine Hotel Company based in Montgomery.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in 1984, Sanders went active duty as a commissioned infantry officer. Similar to numerous infantrymen trying to boost their real-world experience on the civilian side, Sanders put in for a lateral move to change his MOS (military occupational specialty) to data systems officer—now referred to as IT (Information Technology).

“I figured it would be worthwhile for me to have some additional

knowledge and experience when I got out,” Sanders says. After the request was approved, he transferred to I MEF (Marine Expeditionary Force) in San Diego, Calif. Sanders was later relocated to Air Station El Toro in Irvine, Calif., where he worked for the automated service center and ultimately was placed in charge of the information resource center for five years.

“IBM-PC were talked-about items coming online so we were right in the middle of that development,” he reflects on his time there. “Microsoft was bidding for the operating system, which ended up being Microsoft DOS 1.0.”

DOWN RANGE

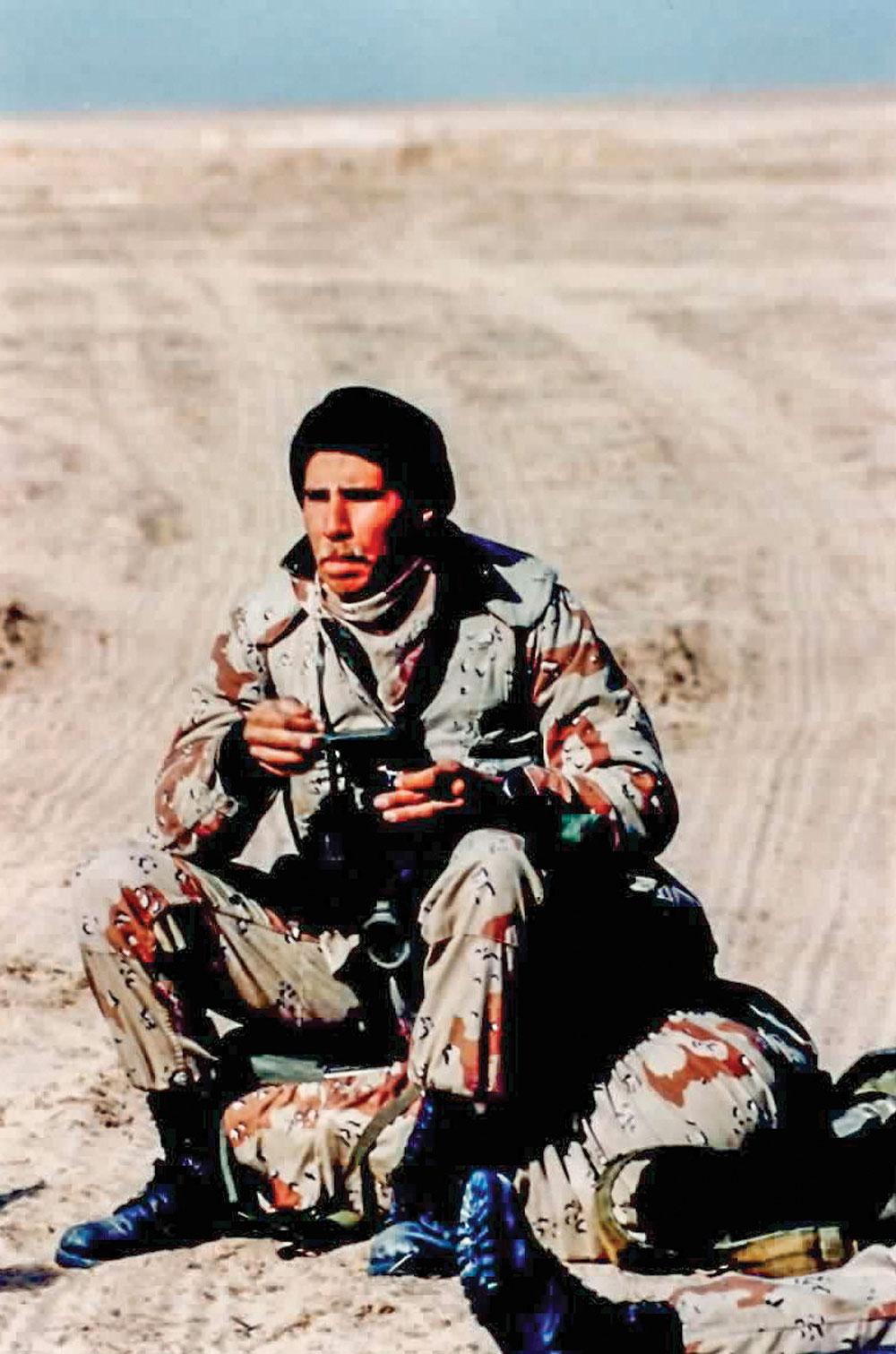

The Marine Corps paid for Sanders to go to graduate school at Auburn University if he drilled with the local reserve unit once a month and two weeks each summer. He had been in grad school less than a year and home from desert training northeast of Twentynine Palms, Calif., for scarcely 48 hours when he got the call.

“We came home from the desert on the last day of July and August 1, Iraq invaded Kuwait,” Sanders recalls. “I said wait a minute, I’m a student! They said no you’re not, you’re a Marine. Pack your bags and let’s go.”

In August, 1990, the Iraqi military invaded the sovereign country of Kuwait under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship in a bid to gain more control over oil supplies along the Persian Gulf coast. Hussein refused to withdraw his troops from Kuwait after being condemned by the United States and UN Security Council, igniting the Persian Gulf War.

Sanders deployed overseas to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, attached to the 8th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, Hotel Company, 1st platoon. His company was transported five miles from the Kuwait-Saudi border around 9 p.m., rucked at pace-count to the border, established a right flank for the battalion and dug in.

“We were close enough that you could see the Iraqis across the border in daylight,” Sanders says. “We lived in a hole all day.” At night they provided interlock patrols or relocated positions and dug new foxholes before the sun came back up. Sanders says his command in Saudi Arabia referred to them as the “speed bump” because they were non-mechanized infantry displaying a show of coalition forces. “We were strict infantry so if they would have attacked with armor they would have went right through us without slowing down.”

The 8th Marine Regiment was in Kuwait longer than any other U.S.

combat unit, Sanders says, not leaving till June 1, 1991, even though President George H. W. Bush had declared a ceasefire on February 28.

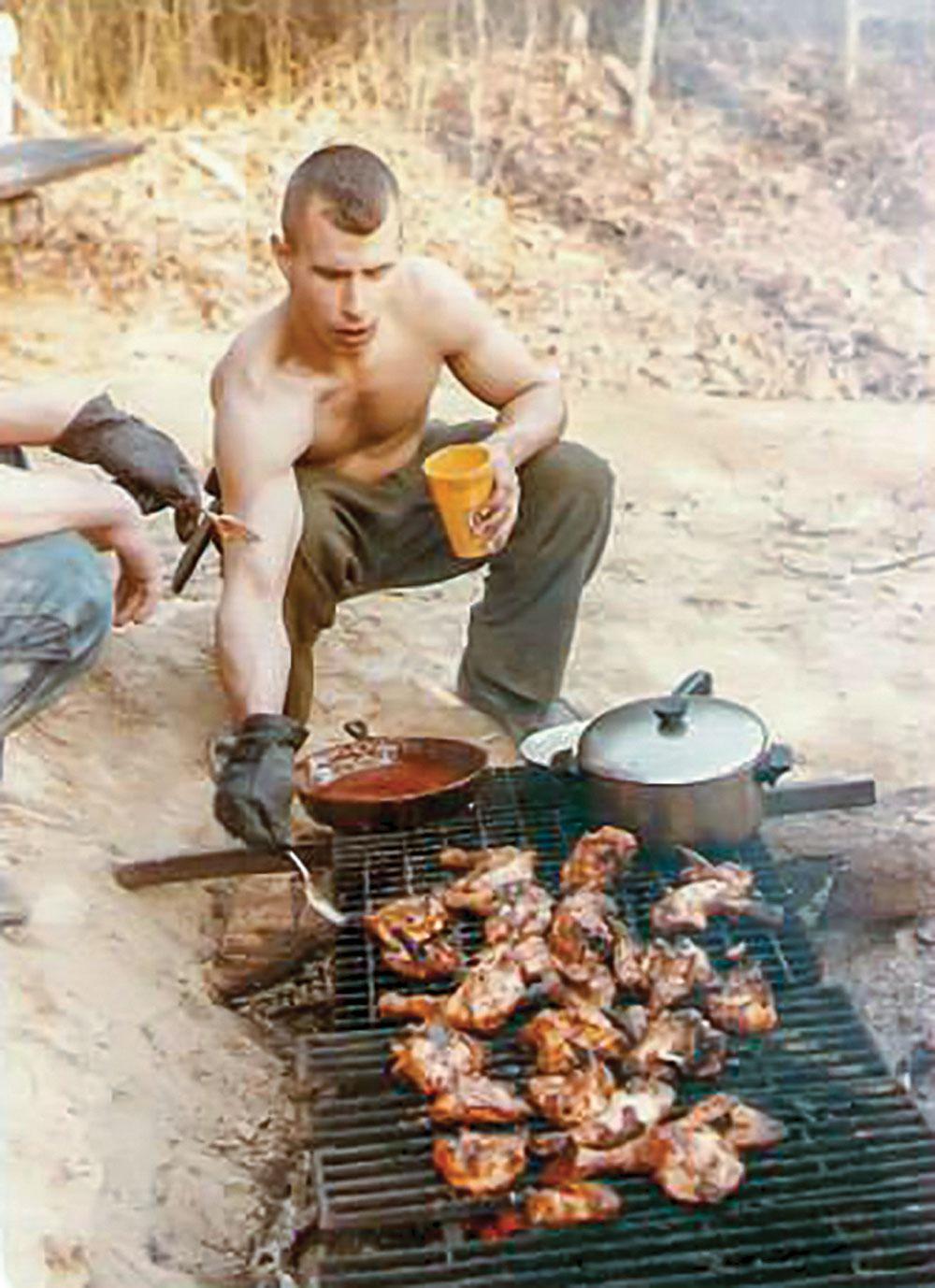

“We went 91 days without hot food, light, no heat, and no change of clothes, living in a hole in the ground,” Sanders says. “You find out pretty quick you can’t get any nastier. But it was a wonderful lifestyle, believe it or not; I enjoyed the hell out of it.”

Sanders received the Navy Achievement Medal, given to junior officers for outstanding achievement, and retired as a Captain.

NEW DIRECTION

When Sanders got back from his tour, his brother Bill asked what he was going to do next. Kirk admitted he didn’t know. The Sanders brothers were considering options over a few beers when Bill had an epiphany. “We had what I like to call a once a great notion,” Sanders laughs, referring to the 1971 logging movie Sometimes a Great Notion (also released under the alternate title Never Give An Inch), starring Paul Newman and Henry Fonda. (Notably, the movie is an adaptation of the 1964 novel by author Ken Kesey, whose first published work was 1962’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Though that earlier story is of course more famous due to the Jack Nicholson film, many critics considered this novel about a family of stubborn Oregon loggers to be Kesey’s finest work, and the film adaptation was also well-received, garnering Academy Award nominations.)

The great notion the Sanders brothers had, Kirk explains: “Bill suggested we get into the logging business and I figured, why not?” They bought a loader, a Mack truck, one skidder and a cut-down machine. Buchanan Lumber donated a trailer and just like that, the newly formed Sanders Timber started logging for the Montgomery mill.

Bill had cruised timber for Buchanan Lumber in the past but other than those summers spent working for Ken Smith, neither of them had a tremendous amount of experience in the woods. They hadn’t grown up in it; their dad was actually a prominent physician. But there was no reason for that to stop them. They were both smart and well educated—both were Huntingdon graduates. Both were artistically talented—Bill was an accomplished painter and Kirk is a writer. Both had served in the military—Bill was an Army Green Beret with the 20th Special Forces group, Birmingham, one of two National Guard groups for the U.S. Army Special Forces. There was no doubt they could succeed here as they had done elsewhere.

HARD HIT

In the spring of ’96 an F2 tornado hit Montgomery, resulting in loss of life and damaged timber. Buchanan Lumber owned a parcel of land along the Macon/ Montgomery county line by Line Creek in Shorter that was damaged. While helping clean up the tract, Kirk was walking through the woods when a wind gust shook a 30 in. pine log out of the canopy above him. It drove him into the ground, immediately knocking him unconscious and into a two-week coma.

The crew had carved a road with a dozer that wasn’t on any map. Even so, “from the time Leroy Howell called 911 to the time I was in the back of the ambulance was eight minutes,” Kirk says. Paramedics conveniently received the call while refueling at a truck stop off the same exit where the Sanders crew was logging. Just as fortunately, the ambulance driver had a hunting lease adjacent to the tract and knew exactly where Kirk was located. They transported him to Jackson Hospital in Montgomery, where he was admitted to intensive care. Once they had him stabilized, he was moved again to the UAB (University of Alabama Birmingham) hospital for surgery.

When he came out of the coma, Kirk couldn’t walk or use his hands.

“The doctors thought I was going to die so they didn’t bother amputating my arm,” Sanders says, noting the 19 pins he now has in his right arm. On heavy doses of pain meds, he was under hospital care for the first year-plus of his rehabilitation. He made good use of the time, though: he wrote a book.

It started with audio recordings he made dictating his memories of his life. Later, to rebuild dexterity in his fingers, he typed a transcription of those tapes. The typing helped repair nerve damage in his hands, he says. The eventual result was a manuscript entitled C.O.T.F.C.: Short Stories of a Marine, a raw and vivid account of his time in the service. The book is now in the Library of Congress.

It took him about five years to fully recover from his injuries, but his outlook on the entire experience remains tellingly sanguine, revealing a lot about the man’s character.

“I tell everybody, I had a good day,” he sums it up. “But that tree died.”

CTL, PONSSE

At the turn of the century in 2000, Sanders heard that Finland based cut-to-length machinery manufacturer Ponsse was looking to expand its presence in the southeastern United States. The logger jumped at the opportunity presented by Ponsse North America President Pekka Ruuskanen. “Pekka said, ‘Why don’t you come with us to Finland,’ so I went.”

At the time, Kirk’s friend Deck Trevitt, the owner of Georgia’s Quality Forest Products, had Ponsse machines but, like many Southern loggers who have tried it, struggled to make the CTL system work in his markets, Sanders says.

“I was in a meeting together with the company owners and told them, ‘I’ll go back to Georgia and show Deck how to run the Ponsses if you will make Deck the representative for the Southeast and when you need to do a demo, use Deck’s machines and don’t worry about transporting machinery because we already got the crew.” They struck a deal and Kirk went to work for Ponsse.

Later, in 2016, Bill bought a Ponsse harvester/forwarder team and the brothers went to work conducting high-grade thinning prescriptions exclusively, which Kirk believes is the future of logging. “We supply grade and preserve a stand of timber,” he says. “We can go in and cut all grade hardwood and in 10 years come back and do it again.”

Now 59, Sanders prefers not to be locked into a fiber contract with surrounding mills, a trick he learned from his brother. “Bill always dealt in hardwood and realized it’s the only way to make money,” Kirk says. “When you have a machine that can find a log in a tree that would otherwise be put in a pulpwood stack, that tree just went up 10 times in value. The way we cut a tree, we cut the logs out and leave the tops sitting there. Only thing coming out is the grade log.”

The harvester, a Ponsse Bear 8WD with two bogies, weighs 62,000 lbs. Its 300HP Mercedes-Benz engine burns about four gallons an hour. Kirk says he uses no more than 500 gallons of fuel a week in both machines combined. A 33 ft. C5 crane boom supports a 4,000 lbs. H8HD processing/harvesting head with four top-and-bottom knives cutting both directions and 10 knives total. Equipped with a gyroscope that keeps the machine level, the H8HD has up to 36,000 lbs. of pulling force and can process 17 ft. a second.

The 40-ton capacity Elephant forwarder is capable of bringing out a full truckload at a time. Its KL100 crane features 36 ft. boom reach and 17,000 lbs. of lift capacity with a 48 in. wide bunching grapple. “It’s way easier when you’re stacking wood, and then you separate your high-end logs and next lower logs,” Sanders explains.

Kirk typically mans the harvester while John Porter drives the forwarder, but both men can run either machine. Jamie Parnell at Equipment Linc Inc., in Maplesville represents Ponsse for the Southeast. Sanders changes oil and filters every 300 hours with Mobil 1 synthetic 10w-40. They use ISO-68 hydraulic oil, grease the head and fill up bar oil daily.

Sanders adds that workers’ comp is considerably less on the CTL operation than with conventional equipment because there’s only two machines in the woods, thus fewer people, lowering the chance of injuries.

Sanders Timber also fields a treelength crew with three Tigercat cutters, two Tigercat loaders with delimber/slasher packages, five Cat skidders and a Cat dozer, motor grader and excavator. While the CTL crew does strictly select cuts of high grade logs, averaging 15 loads a week, the conventional crew hauls 15-20 loads daily of pulpwood, chip-n-saw and everything else. Foreman Richie Smith supervises the treelength side.

NOT FORGOTTEN

Bill Sanders died in May this year at age 60; Southern Loggin’ Times published a tribute to him in the July issue. He’d been having heart problems a few years back and went to the UAB hospital to have a stent put in. The doctors concluded that only three of his valves were functioning; the fourth was closed off.

“The doctors told him he had some sort of heart trauma as a young man and the valve scarred over and rerouted the blood somehow,” Kirk says. “The doctors told him they didn’t know if he had five days or five months.” In fact, Bill lasted another three years.

When Bill was alive, the brothers owned Sanders Timber equally, but they had an agreement that after Bill’s death, Kirk would sign full ownership of the company over to Bill’s daughters, Lou Anne Owens and Mary Buxton, and he was happy to do so. Mary has followed in the family’s other tradition—she’s a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, 5th Marine Regiment stationed in Hawaii. Lou Anne handles all the bookwork for Sanders Timber. With primaries Richie Smith and John Porter supervising the crews and their uncle Kirk describing his role now as “support,” the girls’ inheritance and their father’s legacy seem to be in good hands.

When Bill and Kirk went to work for Ken Smith all those years ago, he was good friends with timber cruiser Buddy Fuzzell. Those two men had gone to college together, and they maintained a friendship with both Sanders brothers through the years. Even after Smith’s death, Fuzzell continued to serve as a mentor to the Sanders. Now, Kirk says, the long-time family friend is taking an active role in seeing Bill’s daughters succeed as well. “He’s helping guide them down the steep and narrow path.”

Through all he’s done in his life, Sanders has maintained the same worldview that sustained him in that hole in the desert almost 30 years ago.

“It’s all a matter of belief,” he confesses. “I believe in God, country and family. There are three things in every man’s life: faith, hope and love. And the greatest is love. Faith in God, hope in your country, love for your family.”